Coastal Tussac and Seabirds

The coastal tussac grasslands of the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) have been a struggle for conservationists. A team of paleoecologists used this grass’s unique characteristics to uncover the ecosystem’s origins, track its changing climate, and reveal why seabirds make these grasslands thrive.

Tussac Grasslands

Tussac (Poa flabellata), a type of tussock grass, forms large peat-producing bunches (tussocks) on the coasts of the Falkland Islands. With all its unique characters, this grass forms the critical layer of these coastal ecosystems.

Tussock, the type of grass

Tussock grasses form “tussocks“—aka, big “beach-balls-covered-in-grass” clumps—instead of lawns. Bunch-tussock grasses are common throughout the world, including the Falkland Islands, New Zealand, and the prairies of the Great Plains.

Tussac, the grass

Tussac grasslands in the Falkland Islands are composed primarily of that one species, Poa flabellata. They can grow meters tall when mature, thanks in part to the pedestals of fibrous growth they form. They also, importantly, deposit extensive layers of peat.

Growth like this creates stability in the ground for burrowing and nesting birds, not to mention the shelter, fodder, and peat they contribute to the ecosystem.

This amazingly important grass is the foundation of the tussac ecosystem, and it’s been difficult for conservationists to re-establish.

mature Tussac grasses grow like the one in the photo below. #tussactuesday pic.twitter.com/4FtW3vz5UR

— Dr. Dulcinea Groff (@DulcineaGroff) September 11, 2018

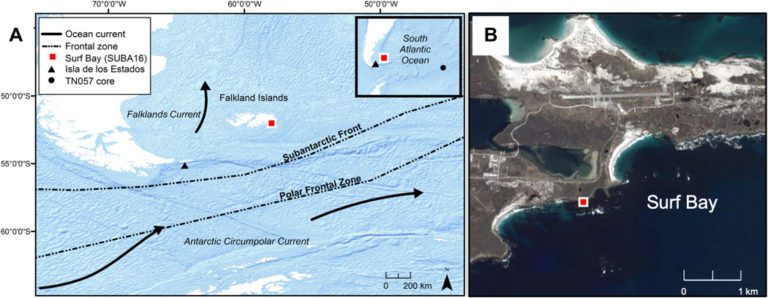

The Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas)

The Falkland Islands, located in the South Atlantic ocean near Argentina, provide seabirds in this region with critical breeding and feeding habitat.

Tussac doesn’t only help the wildlife, though; it helps one of the leading economic forces in the Falklands: wool. Sheep and other introduced grazers feed on the tussac. Problem is, this ecosystem, which historically was only grazed by geese, has seen an 80% reduction in tussac grassland as a result. And that’s a problem everyone wants to solve.

So how can conservationists better reestablish and maintain tussac? Enter paleoecology.

Paleoecology of the Tussac Grasslands

This is where the work of researchers like Dr. Dulcinea Groff and her team came into play. In their 2020 paper, they showed how paleoecology (palaeoecology for our UK friends) could answer critical questions about the origins of these ecosystems by reconstructing a 14,000-year ecological record of the island.

The magic of peat

Paleoecology is a sort of forensic ecology that looks for indirect traces of the past. The team looked at peat deposits for pollen levels, chemicals found in seabird guano, Nitrogen levels, and even traces of charcoal to look for evidence of fire. All of these things would build a picture of how the ecology of this system developed, so they could answer important management questions.

The acidic peat doesn’t preserve things like DNA or bones well, but these indirect indicators are enough to build a reconstructed timeline of events.

PS: Because the peat deposits of tussac decompose, they produce warmth. It’s not uncommon to see seals in a state of absolute relaxation laying on these warm clumps.

An elephant seal enjoying a truly tussac-tasic Tuesday! #TussacTuesday pic.twitter.com/XElK2iEidZ

— Government SGSSI (@GovSGSSI) October 24, 2017

Seabirds came first, and they're critical to tussac

Cause and effect can be difficult to hash out with paleoecology, but this reconstruction laid out a pretty clear series of events.

- Seabirds didn’t colonize the Falklands until about 5,000 years ago.

- Seabirds enriched the land with the ocean nutrients in their poop, and this allowed the tussac to colonize the islands. Tussac benefits from seabird poop.

- Which seabird and seal species used the islands probably changed over time, but it apparently didn’t affect the ecology.

- Seabirds began using the Falkland Islands as a refuge during a time of colder climates.

A question of climate change

It’s encouraging to see a direct relationship like the ones on the Falklands. Allowing better access to tussac by seabirds, or even stocking other birds like chickens, is actionable. It’s also a deceptively simple answer, which needs more work to implement.

Scarier is the implications of climate change, and what a warming South Atlantic Ocean could do to the seabirds living there.

As oceans warm and become less productive, the seabirds that use this landscape could start looking for refuge somewhere else. A scary thought when it turns out these ecosystems depend on their influence. And this could take mere decades to occur.

Conservation work in the Falklands

The encouraging part is that plenty of dedicated citizens, researchers, and conservationists are on the ground working to conserve these ecosystems they love so dearly. South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute is one such organization backing works like this one. Falklands Conservation, another backer of the project, is also actively working to bring back tussacs. Their twitter feed is pretty delightful, too.

#TussacTuesday A Watch Group tussac planting camp on Bleaker Island is an effective pedagogical approach; developing practical conservation skills within our #futuregeneration. #ConservationOptimism pic.twitter.com/v6n3gnZ2wa

— Falklands Conservation (@FI_Conservation) June 18, 2019

#TussacTuesday

— Falklands Conservation (@FI_Conservation) December 29, 2020

Tussac is fabulous for wildlife! If you're in the #Falklands & have a little time on your hands, have a try at growing your own tussac bog. You'll just need to collect a few dry seeds from a large plant and follow these simple instructions: https://t.co/MiUkH4aYbI pic.twitter.com/OoDBHBshAa

Sources/Further Reading:

- Groff, D. V., Hamley, K. M., Lessard, T. J., Greenawalt, K. E., Yasuhara, M., Brickle, P., & Gill, J. L. (2020). Seabird establishment during regional cooling drove a terrestrial ecosystem SHIFT 5000 years ago. Science Advances, 6(43). doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb2788

- Palaeocast Episode 116: Ice Age Palaeoecology, with Dr. Jacquelyn Gill.

- Dr. Jacquelyn Gill / Twitter

- Dr. Dulcinea Groff / Twitter

- Falklands Conservation Registered Charity

Did you spot an error or have questions about this post? Email Rachel Roth.