Dunnarts

What is mouse-sized, carnivorous, and gives birth to tiny fetal joeys? Lots of things probably, but the star this time are dunnarts. Hailing from Australian grasslands, these fat-tailed little marsupials are losing their habitats before we’ve even figured out their social behaviors, but maybe their cute faces will help them sneak into charismatic species status. Let’s show a little love for the little guy.

Cute but fierce

Dunnarts are nocturnal carnivores eating everything from insects and spiders to larger prey like small lizards, frogs, and even other small mammals. Their large eyes give them excellent night vision to help them hunt. They are even known to specifically hunt wolf spiders to reduce competition for the insects they love to eat.

There are 19 species of dunnart which can be as small as 10 grams and about 10-15 centimeters (5-7 inches) long. Half of their body length is tail, which is why they weigh so little.

All species of dunnarts are currently in decline, with a few species reaching threatened status. These very small marsupials have very small home ranges. Because of this, habitat fragmentation is a big concern for them. As new housing developments and farms are built the dunnart is unable to find new space to live. Inappropriate fire regimes (fires that happen too often, are too intense, or are too widespread) are another big threat. A return to traditional Aboriginal fire management is currently being implemented in some areas. A large fire can easily wipe out an entire population of dunnarts.

Another huge threat to dunnarts are feral predators such as red foxes (introduced for fox hunting in the 1800s) and domestic cats.

Masters of Survival

Even with these threats, dunnarts still find a way to survive. One of their biggest adaptations is fat storage. Just as a camel can store fat in it’s hump, these tiny mammals will often store fat in their tail which leads to a carrot-like shape. They aren’t the only animals to store fat in their tails as domestic sheep like the karakul or tunis and many lizards like the leopard gecko will also use similar strategies. For the dunnart, this fat storage is extremely useful in surviving the harsh landscape that is Australia.

Many animals are also known for going into torpor when conditions are hard. This torpor is essentially a deep sleep that lets the animal conserve energy and is fairly common in small mammals in winter. What is very uncommon is going into torpor during pregnancy or while young are still relying on their mother’s milk. Guess who does just that? The dunnart. The ability to go into torpor while nursing is extremely rare as feeding young is very energetically expensive so mammal mothers normally must constantly forage for food to feed themselves and their young. The dunnart meanwhile, babies or no babies, just naps under a nice tussock grass or in a crack in the soil for a bit if it’s a bit cold out.

Marsupial Way of Life

WHY are there so many marsupials in Australia anyway? This is something perhaps not a lot of people think about but we aren’t like much people, so it’s plagued our mind for some time. Turns out, marsupials evolved in North America. That’s right, the continent where today only one marsupial exists (the always-screaming Virginia opossum) gave rise to all marsupials we know today. Those marsupials then moved down into South America where they heavily diversified into many different species. They then arrived in Australia about 55 million years ago (when all these continents were connected by land or nearby islands). Finding a lovely land that other mammals had trouble thriving in, the marsupials took over. About 2/3 of all marsupials alive today live in Australia.

Precocial Babies

Precocial animals are those that at birth are highly developed. For birds and mammals this means they are born feathered or furred but usually still need some care by an adult. How developed a baby is depends on the species. For example in turtles and lizards precocial means hatching from their eggs and scurrying away to find food with little or no parental involvement. Baby ducks are born with feathers and can leave the nest within hours after hatching while Seriema chicks are born with eyes open, but only develop feathers after about a week.

Altricial Babies

Altricial young on the other hand are babies that are born fairly helpless. Baby mice and rats are hairless, blind, and deaf. Many baby songbirds are blind and featherless.

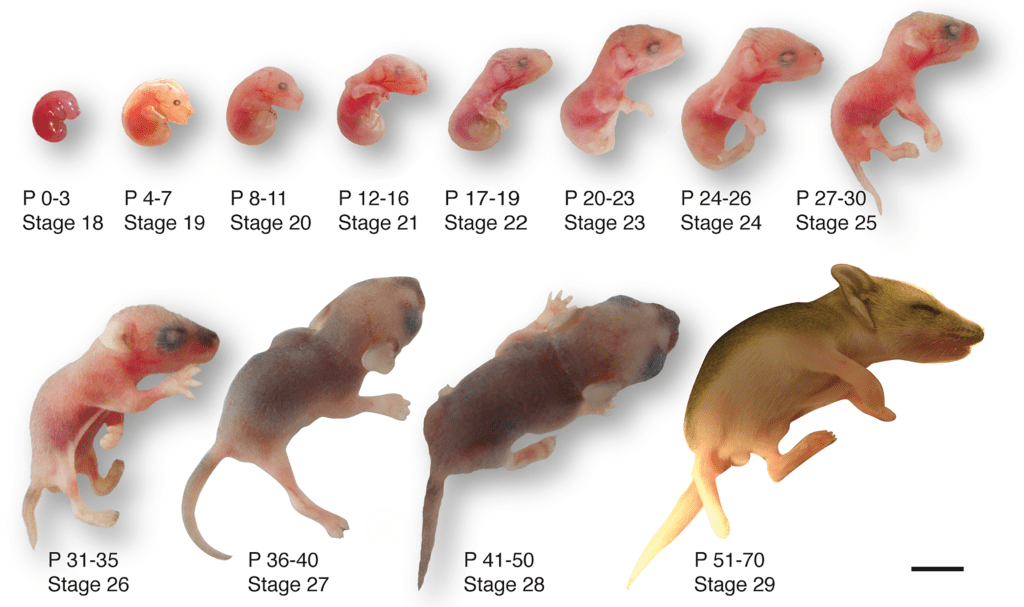

Marsupial mothers are the queens of the altricial method of reproduction. Their babies are not only born as helpless little pink jelly beans, but they are extremely underdeveloped in many other ways as well. Dunnart joeys (as baby marsupials are known) will have back feet fused to their tails into a paddle shape, their lungs barely function, and their skin is thin and translucent. In fact, their skin is so thin that they actually take in most of their oxygen at birth through their skin rather than lungs. Julia Creek Dunnarts in particular have been found to get 90% of their oxygen through their skin after birth. It isn’t until they reach 21 days old that they start getting more than 50% of their oxygen through their still developing lungs.

Benefits to Joeys

There are a lot of benefits to the marsupial way of life. Since their joeys are so underdeveloped gestation is very short in marsupials. There’s the amazing 11 day gestation of the stripe-faced dunnart, but others have similarly short gestations including: Virginia opossum (13 days), wombat (20 days), kangaroos and koalas (30-34 days). Compared to an animal like a goat which is 150 days or an elephant who is pregnant for a whopping 645 days the marsupial pregnancy is remarkably short!

Have a short pregnancy means the mom isn’t gaining a lot of weight to slow her down and she also isn’t spending a ton of resources on the baby before it is born. So, as harsh as it may sound if she loses a few babies, it’s not a huge loss. After birth, marsupial moms are well-documented in sacrificing their babies to save themselves. The pouch they carry their joeys in is surrounded by muscles, and by relaxing those muscles they can drop their babies as a distraction if being chased by a predator.

Marsupials also have a very unique reproductive system that allows them to essentially be eternally pregnant. When compared to placental mammals their reproductive system is doubled. They have two uteri that can grow two litters and even two vaginas leading to those uteri. As one litter is nursing in the pouch, mom can also have a new litter growing in her uterus ready to be born as soon as the pouched litter leaves. They are even capable of embryonic diapause in which they halt the development of a growing litter. This is helpful if extreme conditions exist so they can wait until conditions improve.

How to Help:

Truly, dunnarts (and marsupials) are amazing animals worthy of our fascination. As mentioned, a few dunnart species considered threatened and most (if not all of them) are seeing a decline in population numbers. But all is not lost, and there are some easy ways that we can help them bounce back. A big help to these guys is controlled burns, especially if it can be done in small patches leaving areas for them to retreat to. Controlling grazing is also important, and making sure that livestock are not overstocked and rotated if possible to allow vegetation to grow and recover. Feral livestock (including camels!) are an issue as well for animals throughout Australia so controlling their numbers is a constant battle.

And of course: keep your cats indoors.

Sources/Further Reading:

- Curnow, C., Lewis, P., et al. About the Dunnart. World Wildlife Fund. Accessed 12 March 2021.

- Dunnarts. Bush Heritage Australia. Accessed 12 March 2021.

- Geggel, L. Why Are There So Many Marsupials in Australia? LiveScience, 3 Mar. 2019.

- Suárez, R., Paolino, A., et al. (2017). Development of body, head and brain features in the Australian fat-tailed dunnart. PLoS ONE 12(9).

- Walker, K. (June 2012). Husbandry Guidelines Fat-Tailed Dunnart. Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond.

- Jackson, S. (2003). Australian Mammals: Biology and Captive Management. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 0643066357.

Did you spot an error or have questions about this post? Email Nicole Brown.